by Gretchen Wing

Lance Brittain is a practitioner of “Black Arts”– not witchcraft, but a melding of elements “too complicated to model mathematically: fire, furnaces, casting metal …” His life is similarly melded: past and present, coast and heartland, art and science, folks from every walk of life.

So fascinated is Lance with history, our interview could have stuck there. Between his mother’s family – 1850’s Oregon Territory loggers, railroad men from New York – and his father’s – traced from 1690 North Carolina to Mississippi – it’s difficult to pry ourselves away. There’s the 1849 family Bible; there’s the female ancestor who founded Louisiana State’s English Department. But Lance’s story really starts when the Brittain family lost its mercantile business in the Depression and his father joined the Navy, meeting Lance’s mother in Seattle.

Navy brats move frequently, across the continent. But by age eight Lance and family settled in Seattle, where he started playing his mom’s guitar. The instrument was too big, so in school he switched to trombone. Lance studied with “an old-time road musician” who formed his students into a 12-piece swing band, which performed throughout Seattle. Thus, adolescent Lance’s first gigs included the 1962 World’s Fair.

When the family moved to Pennsylvania, Lance added another ingredient to his future: language – specifically, German, learned from Amish teachers at his small high school. After graduation in 1967 he worked as a trash burner in a hospital boiler room, demonstrating an early love of fire, and ability to thrive on diversity, as “I was the only white boy.” Then, “homesick for Puget Sound,” he headed to University of Washington.

A ceramic engineering major, Lance mostly “toed the line,” despite attending some Vietnam demonstrations. A draft number of 365 enabled him to leave school for a year to work at a ceramics factory in Munich. Amidst a diverse immigrant work force, he used his German to become the shop floor translator.

After some traveling, Lance finished his UW degree in 1972, just in time for the Boeing Bust. But he got an offer from the 80-year-old stoneware company in Illinois, new territory for him. There, as Plant Ceramist, Lance became “keeper of the formulas” of the pottery. He proudly shows off blue-and-white water crocks and iconic Jack Daniels whiskey jugs.

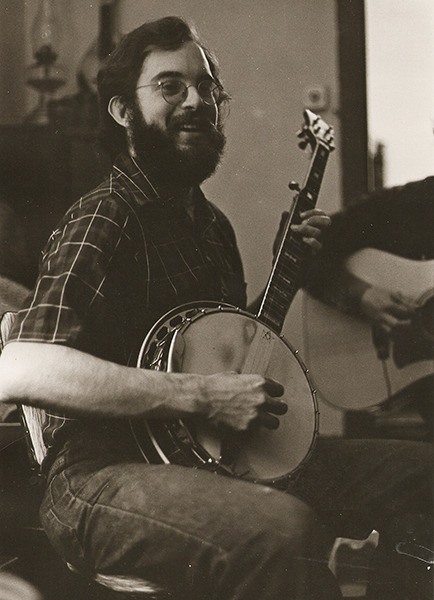

In Illinois Lance added Spanish to his fluency list, thanks to his mostly Mexican workers. “I’d go hang out and party with the Mexicans, playing Tex-Mex music,” he says. He also brought together old-time musicians with youngsters from the local university. By 1974 his band Shady Grove formed; they made a double album in Nashville and still stage musical reunions today.

But at work, Lance was “getting a little bored,” so he joined a friend to homestead in the Ozarks of Arkansas. They bought 120 acres and, along with some “back-to-the-landers” from California, soon owned “an entire holler,” where they quarried stone and built a timber-framed home. In winter they migrated as tree planters across the south. “I’ve probably planted 300,000 trees in my time,” Lance muses.

He dreamed of opening a pottery studio, but the holler was too remote. Closer to hand was Lil Shaffer, one of the Californians, who eventually married him.

Back in Washington for his mother’s funeral in 1979, Lance was recruited to work part-time at a small stoneware factory in Seattle, allowing him to continue his Arkansas homesteading. But in 1985 the factory closed, and Lance, now married to Lil, decided to change his skill set. (“Part of my story is staying one step ahead of companies getting liquidated,” he jokes.) When some metallurgist buddies invited him into a medical device startup, Lance found himself embarking on a new high-tech career, an MBA program, and fatherhood … in one three-week period. While Lil minded their daughter, Lance worked days and attended night classes paid for by Coopervision.

In 1989, Coopervision was bought, and Lance spent the next seven years with Spectrum Glass — “back to fire/smoke/furnaces,” he laughs — melting 20 tons of glass per day for stained glass artists. After one last “black arts” gig in Bothel, plus another six months in downtown Seattle, Lance was ready to return to homesteading, this time on Lopez.

In the ‘60s Lance’s father and much-older brother had bought Lopez land and taken Lance camping. Now he and Lil came over on bikes to investigate. In classic Lopez style, they built their house on weekends, moving permanently in 2005. Nowadays, a blend of projects keeps Lance mostly at home. Besides building and gardening, there’s his weekly KLOI show, The Grand Central Vocal and Plectrophonic Review. Lacking a band like Shady Grove, Lance plays music all over Lopez – at Vita’s, for example, or for KLOI.

“To become an expert in black arts processes,” Lance states, “you need the discipline of careful observation. Same with music.”

So when you see Lance onstage, pausing to listen to his fellow musicians, remember: you’re watching a wizard.