by Gretchen Wing

Robert and Vivian Burt were invited to dinner at the home of a Lopez acquaintance. Looking over their field, Robert commented, “I first ploughed that when I was twelve…You got a couple damp spots over there you gotta watch.” 68 years later, even jokingly, Robert still applies himself to maintaining the island the way it deserves.

Given Burt Road, Robert’s deep Lopez roots are no surprise. His great-aunt Isabelle Bloor’s original deed stretched from Hoedemakers’ Farm to Davis Point. Grandfather John Burt visited from Iowa in 1902 to help build Center and Mud Bay schools, and in 1906, when John’s wife died, he returned with his five children. As Robert’s dad, Ray, grew up, farming provided only a partial living, so he took off for Alaska most summers to buy fish and repair canning machinery. Robert seems to have inherited all the “fixit” genes of his forebears.

Youngest of four, Robert was delivered by his grandma in a farmhouse off Davis Bay Road. Like his father, he worked from the get-go. The family’s draft horses were too big for him to handle. But tractors? No problem, starting at age six.

The family kept dairy cows, selling cream for San Juan Gold butter. Dairy chores are constant as tides—sometimes with beneficial results. “I got my hand busted up,” Robert says, “and the doctor told my dad, ‘You’re going to have to get a sponge-rubber ball for him to squeeze, or he’ll lose the use of that hand.’ My dad told him, ‘He don’t need a sponge-rubber ball, he’s got 29 cows to milk, night and morning.’ So those cows saved that hand.”

Starting at the Center School (now the Grange) which his grandpa had built, Robert and his three cousins finished at Port Stanley. Until then, Lopez students had to leave for San Juan or even Sedro-Woolley to graduate, as Lopez’s schools weren’t fully accredited. But the Burt boys worked on Lopez and couldn’t spend their senior year commuting. So they petitioned the Superintendent to finish accreditation. In 1951, Robert and his cousins became Lopez’s first graduating class.

Characteristically, Robert played a major role in the renovation of Port Stanley schoolhouse. When the grateful committee presented him with a plaque, someone asked him what it said. “Oh, heck, I can’t read,” Robert joked, making fun of the school that had fostered him. His hours of work, though, restoring a rotted, animal-infested structure to its former glory, demonstrate his real affection for the place.

After graduation Robert was ready to try the wider world. He got a job with Boeing, but found it “too tough.” What could possibly be too tough for this farm kid? “They put me in the experimental division, making B-52s. But the B-52 was out flying, so there was nothing for me to do. I’d sit at the desk, look at the blueprint…I’d be falling asleep. I told ‘em, ‘I can’t do this.’”

Boeing did avail itself of Robert’s machinist skills, but not enough for his liking, so he took a job at a Ford dealership that included an apprenticeship program. Back on the farm, Robert had learned through improvisation, but now, night classes taught him proper methods. His job with Ford lasted 17 years.

Eventually management changed, though, and Robert became disillusioned hearing customers complain about things he couldn’t control. So he hired on with Seattle School District, maintaining their fleet of vehicles, “over 300 pieces of equipment.” He stayed with SSD for 25 years, becoming general foreman, keeping things running.

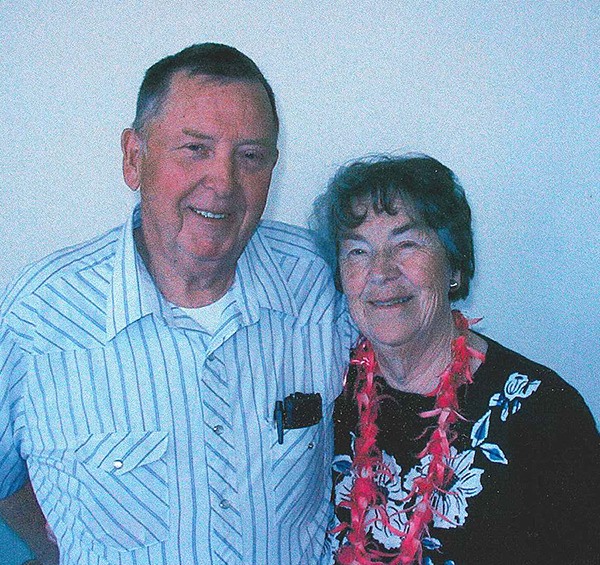

Much as he loves it, work alone does not define Robert’s life. “The best thing that ever happened to me is sittin’ over there,” Robert says, gesturing to Vivian. In 1954, they met at a Scandinavian dance in Kenmore. They married the next year; a son and two daughters followed. Vivian left teaching to stay home with the kids, then worked as a substitute for 13 years, before ending up as a federal employee.

The Burts built a house in Lynwood, “keeping our nose to the grindstone,” as Vivian puts it, but Lopez always beckoned. They built their Skid Road house here for vacations, “one board at a time” on weekends. Finally, “42 years of working was enough,” and they became Lopezians—in Robert’s case, again. Their son bought their Lynwood home. “He hasn’t changed the locks yet,” Robert deadpans, “although he has put in an alarm system and he hasn’t told us the code…”

On Lopez, Robert and Vivian are in great demand. The Historical Society taps them for its advisory board, and sells cards featuring photos taken by Robert’s grandfather. Projects like the renovation of the Grange take advantage of both Robert’s carpentry skills and his memories. The Senior Center is another major component of the Burts’ Lopez maintenance campaign. Robert was chairman; Vivian currently serves as substitute secretary. Both attend Senior Lunch regularly. “We try to encourage people to come, to stay and talk,” Robert says. “Eventually, you’re gonna need it.”

The Burt property has already hosted one grandchild’s wedding, with two more to come, demonstrating how Robert and Vivian have kept Lopez vibrant for following generations. Approaching the house, one sees a refurbished 1928 Model A, and some old tractors Robert has “saved.” Yes, the couple travels quite a bit—to Europe and Scandinavia—and yes, Robert possesses other talents, like crafting musical instruments. But his true vocation is keeping things running.