By Gretchen Wing

Metallurgy, n. 1. The technique or science of working or heating metals so as to give them certain shapes or properties.

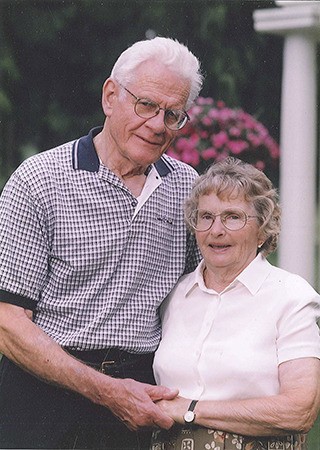

Doug Allan is a man of metal.

From high school shop to apprenticeship, from soldier to salesman to business owner, Doug has built his career around the fact that metal molecules rearrange themselves in high heat, and toughen up.

Shortly after Doug was born in Aberdeen in 1924, his dad was killed in an auto accident, so Doug and his mother moved to Bellingham where his grandmother ran a boarding house.

There his mother, a teacher, met and married Mitch, another teacher, but Doug was already forging his independent spirit and didn’t bond tightly with his new stepfather.

“I basically took care of myself from the age of eight,” he says.

The small unit –“my mom and Mitch and I,” Doug says, avoiding the word “family” – moved next to Sunnyside, in Yakima County, where Doug’s mother and Mitch co-taught in a two-room rural school. Doug liked school just fine, but childhood memories don’t elicit any specific passions or delights.

“Survival,” he says, “was more important.”

In his teen years, Doug moved back north, attending Everett High and working in the new family business, a service station. His future wife, Barbara, would stop in to have her bike tires filled, but Doug is all business with these memories.

School, then work, squeezing in homework between customers – those were his life rhythms. Then, during his junior year, he moved in with his aunt and uncle in Mt. Vernon and went to work in their machine shop.

Doug “didn’t like machining worth a damn,” but the blacksmith shop called to him. Forging metal – now that was something.

A football scholarship – Doug’s a big guy – led back to Bellingham and Western Washington University, but Doug only stayed there a year before enlisting in the Army. It was 1943, and his skills were in high demand. His unit followed the troops into Europe six days after D-Day, working to repair jeeps and trucks as fast as they broke down.

During the Battle of the Bulge they came under fire, but Doug doesn’t care to talk much about the war. More important is the fact that, after a short stint at Everett Community College, he finished his degree in industrial management at University of Washington, and there he met Barbara.

This time he remembered her as more than the girl who came in to fill her tires, and the two married, in 1949, as soon as he graduated.

In the postwar economy, Doug found a job right away… but not in metal. In sales. Of ketchup. Or Heinz 57, to be exact.

The Allans settled in Bremerton and started a family as Doug drove and drove and drove. This was the beginning of “thousands of miles” of sales-related travel – yet another part of Doug’s personal refining process. But after a year and a half, he switched to selling a more familiar commodity: welding equipment and oxygen tanks.

Metal called once more. And when a bankrupt metallurgy company became available for sale, Doug answered the call.

The result was the Allan Family LLC in Kirkland, and a 47-year career of heat-treating steel to meet the demands of aircraft.

The process, Doug explains, “is the same today as it was 300 years ago.”

When steel is heated to 1,500 degrees, molecules move, and when quenched in oil and water, added alloys are bonded tightly enough to withstand the 300,000 pounds-per-square inch of pressure that some airplane parts require. Doug rattles off these statistics as though we were discussing the weather, defining the process of metallurgical transformation as “increasing the tensile strength of metal” – and he makes sure the interviewer can pronounce the word “metallurgical.”

Now this is a comfortable topic.

But the interviewer, of course, wants to know how Doug and Barbara came to Lopez. As with many Lopezians, their foothold began as a vacation cabin back in 1985, and they and their four daughters spent an increasing number of weekends learning to feel at home here. Not until 2010 did the couple become full-timers, after Doug had sold the family business to his eldest daughter, who still runs it along with her son.

Until recently, the Allans made regular trips back to Seattle for Husky football games.

Now, as they deal with Barbara’s Alzheimers, the Allans are considering a permanent move there, for more comprehensive care. With “nine or ten” grandchildren, their Lopez house will probably stay in the family, but, as Doug says, “Whatever comes, comes.”

Doug concludes our interview in simple understatement: “Metal has been a big part of my life.”

This appears to be true both literally and metaphorically, for a man whose ability to respond to life’s pressures has clearly been well forged