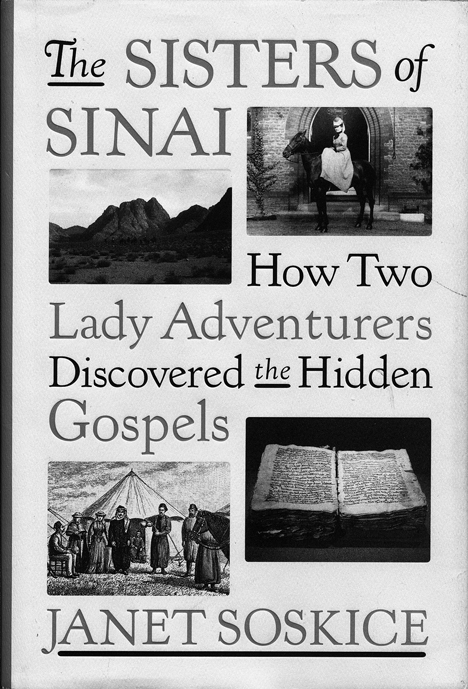

1892, Agnes and Margaret Smith, plucky twins from Scotland, made a momentous discovery at the library of St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mt. Sinai.

To this day, the neglected palimpsest remains the earliest known copy of the Four Gospels.

This particular manuscript was written in ancient Syriac, the language spoken by Jesus.

In The Sisters of Sinai, author Janet Soskice, takes us on the life journey of the two identical twins.

Their father, John Smith an attorney and widower, raised his two daughters in a Presbyterian environment, rich in education and exercise with few girly frills.

He found they had a penchant for languages and encouraged their education.

Each learned French, German, Spanish and Italian while quite young and were given trips to those countries as a reward for their diligence.

Mr. Smith, a self-made man and prominent citizen of his community, came into a rather large inheritance from a distant relative.

He was able to make substantial investments with the monies and by the time of his sudden and pre-mature death, left the twins a great fortune.

After their father’s death, the twins planned a trip down the Nile. This would be the first of many extensive journeys to the Holy Land.

The first trip to the Holy Land, although problematic, merely wet their appetites for adventure. Upon arriving home, Margaret met James Gibson her fiancé for the next ten years.

Agnes began writing novels and travel books. This led to another trip to the Holy Land—more specifically Greece where they learned Greek.

Some years later after the sudden death of Margaret’s new husband, they planned another trip east.

This time they set their sites toward the recently opened Suez Canal and then onto St, Catherine’s. Why not they thought?

There would be several more trips to Egypt and Jerusalem that eventually led them to St. Catherine’s dark closet where the palimpsest was stored. And, more languages to learn, camels to ride, photography methods to master before they could determine the breadth of their discovery.

Even though they had been told the monks of St. Catherine’s were unfriendly and uncooperative to foreigners, the twins found a warm and supporting group of monks, willing to help them.

It took some weeks to carefully photograph the vellum pages. They had to steam the book to separate each page in order to photograph the ancient work.

They traveled back to Scotland excited about their find, making plans to have the photos, once developed, inspected by experts.

Little did they know what kind of drama awaited them upon arrival and with the subsequent association with “experts”.

It is to the twin’s credit and their Presbyterian upbringing that they persevered though deception, misunderstanding and periods of abject conjecture about their original intent for the ancient document.

In the end, they were honored scholars, credited with many old manuscripts translated and catalogued—both at St. Catherine’s and within the British Empire. Cambridge became their home of record where they lived full and long lives at their home, Castlebrae.