By Lexy Aydelotte

Weekly contributor

Shayar Valandro is an underwater forager. A strange kind of fisherman who scours the sea-floor for edible gold. He is looking for uni, the gold-colored reproductive organ of a sea urchin. It fetches a high price in restaurants, and Valandro knows where to find them.

Washington’s urchin fishery is thriving. This season almost 300,000 pounds of urchins have been caught in the San Juan Islands, and prices are up. The green urchin fishery is still open but fishing for reds closed on Feb. 8 when the quota was met.

Though the U.S. Coast Guard predicted gale force winds later in the day, and rain was already pouring down, but neither Valandro nor his deckhand Tai Kaulana seemed concerned as they sped off toward dark clouds and an undisclosed location near Stuart Island.

It’s undisclosed because Valandro doesn’t want other divers to find his favorite spots.

“It’s not like there are just urchins everywhere,” Valandro said. “You don’t want to sit around telling your buddies where you go.”

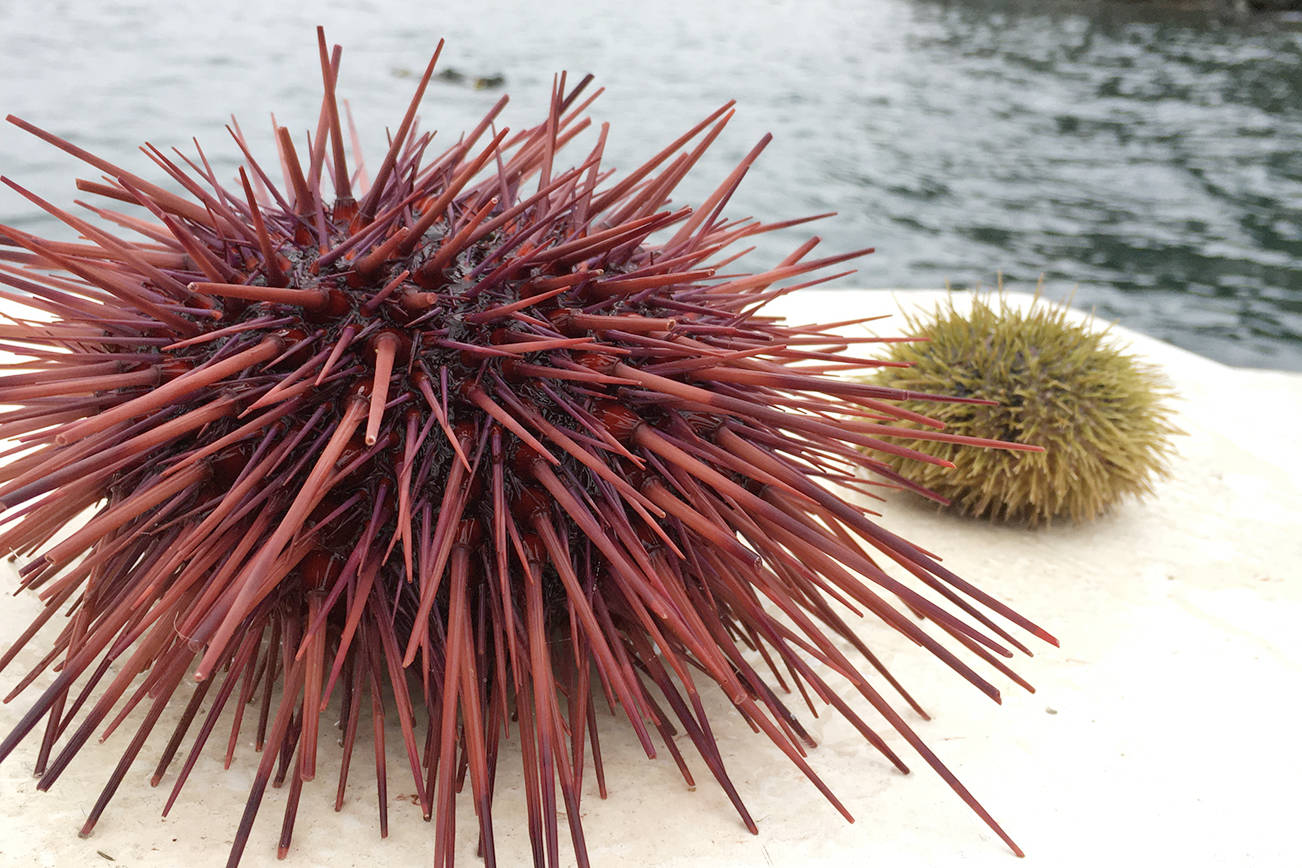

But there are a lot of urchins. Of the four species of urchins that live in Washington, two are commercially harvested — the larger red urchins and the smaller greens that Valandro was after.

“There is a little overlap in habitat, but they tend to concentrate in different areas,” said Taylor Frierson, a Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife biologist and the sea urchin and sea cucumber fishery manager.

The concentrated clusters are called beds and they can cover vast areas. But divers don’t pick up all the urchins they find; there is a size limit and divers have an interest in leaving behind enough urchins to repopulate the bed.

“We go back to the same spots year after year,” Valandro said. “It’s just like mushroom foraging.”

But mushroom hunters don’t have to stare down Steller sea lions, contend with strong currents or breathe through a hose attached to an air compressor. Compared to urchin diving, mushroom foraging seems like a walk in the park.

When the vessel reached its destination, Valandro squeezed into his leaky drysuit, put on 35 pounds of lead weight to help him sink, and jumped overboard into the murky-green water.

The 27-foot boat was anchored precariously close to a rocky cliff, so Valandro wrapped the anchor around a rock to try and stop the boat from dragging toward the shore. It didn’t help. Kaulana kept having to jump onto the swim step to fire up the outboard and steer the boat away from disaster.

“The best urchins live along the kelp line in shallow water, and the most productive beds are usually where there is a pretty strong current,” Valandro said.

This combination can be dangerous for divers and crew. In a strong current, a diver has to hold on to something or struggle just to stay in the same place. Winter storms and swells from passing ships threaten to smash divers and boats against the rocks.

“I don’t recall any recent deaths, but I do hear of people getting hurt,” Frierson said. “Most often, it’s decompression sickness.”

A condition caused by rapid pressure changes, like ascending too quickly while SCUBA diving, decompression sickness causes nitrogen bubbles to form in the body and can be fatal.

But most urchin divers don’t use SCUBA tanks, Valandro explained. They’re bulky and expensive to fill. Instead, they use a hookah system, he continued, which is basically an air compressor that pumps air through a hose to the diver.

Kaulana fires up the boat’s air compressor for Valandro — it is loud and unrelenting. If it broke, Valandro wouldn’t be able to get air. So Kaulana’s job is to make sure that doesn’t happen. He watches the hose to make sure it doesn’t get kinked or tangled, diligently coiling and uncoiling it as Valandro moves around underwater.

Every hour or so, Valandro came to the surface with a net full of green urchins, weighing close to 200 pounds. Kaulana used a small crane to lift the net onto the boat and then immediately covered the urchins with a tarp. Urchins don’t like rain, according to Valandro.

“Freshwater will kill them. Their spines will turn brown and they’re not good after that,” Valandro said.

It can be difficult to determine the quality of the uni without cracking them open. But the condition of the spines can tell you how many times they’ve been handled. More broken spines mean the urchin might not be as fresh, so divers try to handle them with care, even when they’re catching more than a thousand pounds a day.

Another big factor in determining quality is the season. The commercial harvest begins in September and the quality starts to decline in early spring when the urchins start spawning.

Washington urchin is listed as a “best choice” by Monterey Bay Aquarium’s SeaWatch program, which publishes a list of sustainable recommendations for seafood consumers.

Frierson said this rating has a lot to do with management practices. WDFW conducts regular dive surveys to determine the health of the urchin population and to set quotas for the commercial fishery. The harvest rate is currently set at 4 percent of the total biomass. So roughly 96 percent of urchins are left alone.

Nick Coffey, chef and owner of Ursa Minor, a hyper-local restaurant on Lopez Island, said he wishes he could serve more urchin.

“Urchin is the hardest local product to source,” Coffey explained. “Maybe something else is harder, but I don’t want it. Last year we didn’t have them on the menu. I just couldn’t find a good connection.”

This is surprising, considering the San Juan Islands harvest more urchins than any district in Washington. So why can’t local restaurants get urchins?

Part of the problem is that most of the demand is coming from Japan. Coffey only needs about 10 urchins a week to have them on his menu. So even though restaurants are willing to pay more, they don’t have enough demand to justify the time and energy it takes to deliver them locally.

But Coffey said he won’t stop trying and added that he reaches out to other chefs and seafood distributors whenever he can.

“It really represents the islands. It’s rarefied and decadent,” Coffey said. “They’re not salty like oysters, but they do have a subtle essence of the sea.”

Urchin is rich and fresh, almost fruity, like citrus without the acidity. The texture is smooth and velvety.

“If someone hasn’t tried urchin they should, it’s like jumping into a cold body of water you just have to do it and then it’ll be really enjoyable,” Coffey said.

The storm started picking up as Valandro and Kaulana returned to Friday Harbor. They had caught about 1,200 pounds of green urchins, and they loaded them all into the back of Valandro’s pick-up truck to drive them onto the ferry to sail to Anacortes, where a buyer would pick them up and put them on a plane to Japan.

The San Juan Islands are fortunate to have so many culinary delights. They’re famous for salmon, oysters, even gooey-ducks, but uni is so often overlooked. It really is a hidden treasure in the Salish Sea.